I think one thing the reader must keep firmly in mind when reading anything by Gene Wolfe is that Wolfe likes to play with your head — and he seems to have developed an admirable store of ways to do it.

I think one thing the reader must keep firmly in mind when reading anything by Gene Wolfe is that Wolfe likes to play with your head — and he seems to have developed an admirable store of ways to do it.

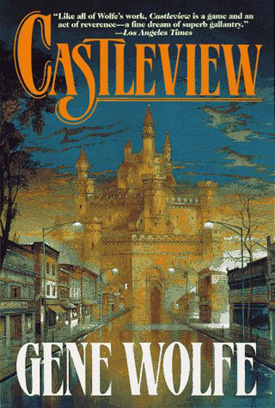

Castleview is a small town about thirty miles from Galena, which puts it in the northwest corner of Illinois. It got its name because some people can, when conditions are right, see a large castle in the distance. There are as many explanations for this phenomenon as there are skeptics. Will Shields has just bought the town auto dealership, and he and his wife, Ann Schindler, are looking at the Howard house with their daughter, Mercedes (named for the car, which was, in turn, named for its creator’s daughter: there’s a nice symmetry there). As they are talking to Sally Howard and her son Seth, word comes that Tom Howard has been seriously injured. Later, as Will is investigating the County Museum for information about the castle (which he saw from the attic), and Ann is investigating a nearby girls’ riding camp for information about a horseman that they had nearly run down earlier, Seth Howard shows up at their motel and invites Mercedes for a drive up to a local lookout point, where they might see the castle. Then things start to get complicated.

The overtly fantastic part of this story is Wolfe’s interweaving of contemporary small-town America and the archetypes of the Arthur Cycle. The archetypes are variations on what we have come to think of as the “fantasy heroes” of legend, and grow directly out of Wolfe’s somewhat darkside approach. They remind me of nothing so much as Elizabeth Bear’s take in Blood and Iron, but only because I read Bear’s book first. (I might also add that Arthur himself, although he is a character in the book, is disguised until the very end.)

Wolfe’s play-with-their-heads device in this one is similar to the method by which the film Alien built the tension to the screaming point but never let you scream: he repeatedly cuts to a new scene just as some potentially significant event happens or is about to happen — the phone rings, but we don’t find out right then (if ever) who it is or what they want, because he moves us to another scene and another point of view. It’s a great way to get your audience keyed up.

The climax is a surprise, and his way of dealing with it — by not really “reporting” it — leads us into an epilogue in which all is made clear, if you’re willing to think about it for a bit.

This is not one of Wolfe’s high-profile books, but it’s an intriguing take on the Arthur legend and of course, it’s a good read.

(Tor Books, 1997)