Rebecca Scott penned this review.

Rebecca Scott penned this review.

“To absent friends, lost loves, old gods, and the season of mists; and may each and every one of us always give the devils his due.” –Hob Gadling’s toast

When his sister Death shames him with it, Dream finally admits that he was wrong to condemn Nada to Hell, ten thousand years ago, for refusing to be his queen. Having owned up, the only thing he can do is to go and release her and tell her that she is forgiven. There’s only one problem: Lucifer has sworn to destroy Morpheus for embarrassing him before all the Hordes of Hell. Nonetheless, to Hell Morpheus will go.

But when he gets there, he find the Hell of Lucifer empty, and its resigning master locking the last gates. Rather than fight him, Lucifer gives Dream a gift, the Key to Hell. Dream doesn’t want it… but everyone else does.

Gaiman began planning this story when he was writing issue 4, which depicted the Sandman going to Hell to retrieve his Helm, lost these many years and in the posession of a demon. On that fateful visit to Hell, Morpheus sees Nada, his old love, whom he still loves but has never forgiven. At the time, we got no further story on her. Five months later, we got her backstory, in “Tales in the Sand.” Nada had been an African queen who had refused Dream because it was not given to mortals to love the Endless. Having watched her city destroyed, she died rather than bring more danger upon the people. Having died, she let Dream sentence her to Hell, until he should stand before her and tell her that she was forgiven, rather than be his Queen of Dreams.

And, a year after that, we finally found out what happened next.

This collection is a feast for lovers of mythology, even those who (like me) are sticklers for accuracy. Odin cannot think or remember without Huginn and Muninn, the ravens Thought and Memory. Thor is redheaded and bearded. Loki is handsome despite the scars around his mouth. Egyptian, Japanese, and Judeo-Christian figures are similarly well depicted. And the representatives of Queen Titania are simply charming.

Season of Mists also introduces us to two more members of Dream’s family, and introduces us more thoroughly to the members of whom we are already aware. Destiny and Delirium are the oldest and youngest of the Endless; Destiny is a tall figure in a grey robe, chained to a book; his youngest sister (who used to be called Delight) is a childlike waif with mad-colored hair and odd-colored eyes. The brief essays describing each of the Endless are both lovely and enlightening.

But, we become aware, there is one of the Endless to whom we have not been introduced, and whose name has not yet been revealed. Nor is it here: he is known only as “the prodigal.”

In previous stories, Dream has shown a very limited range of emotions. Now, we see that range expanded. He is shocked, touched, wistful, worried, and dumbstruck. It’s a measure of how much he has changed, and is changing, that we see so much when he’s under stress. He dons again his obdurate mask, as soon as he can, but we can see a little tenderness gleaming through the cracks in his armor.

Hell, in the world of The Sandman, is not a place where a vengeful deity sends those who have offended Him. Instead, it is a place where dead mortals choose to go (presumably without realizing that the choice is theirs) if they believe that they have sinned. It is, perhaps, also less of a place than a state of mind.

If Hell is not what we expect, then what is Lucifer? He is neither the Root of All Evil (“‘The Devil made me do it.’ I have never made one of them do anything. Never,” he protests), nor soul-monger (“How can anyone own a soul?” he asks). Instead, he is disillusioned and world-weary, and ready to try something new. He is cruel enough to giggle at what he’s putting Dream through, and kind enough to compliment the Daughter of Lilith who loves him. He is embittered at the realization that even his great rebellion is part of his Creator’s plan, but not so much that he cannot appreciate a sunset as His work.

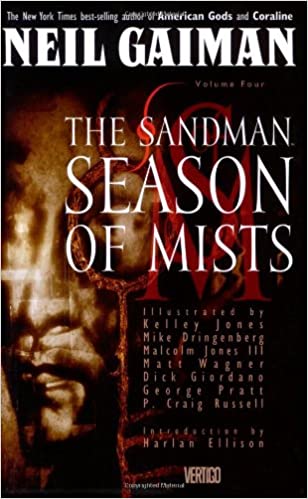

The artwork… I can only praise Mike Dringenberg and Malcolm Jones III so many times. Their styles and Gaiman’s are well-suited. But this volume also features a number of other artists. Kelley Jones’ gods and demons, and especially his Lucifer, are wonderful. Matt Wagner’s returned dead are disgusting, charming, or horrifying, exactly when and how they ought to be. My only complaint on the artwork is that the shadows are sometimes too thick and black, losing some expression and character.

Episode four of this story follows Gaiman’s tradition of inserting a seemingly separate story which serves to point up the central themes of the greater story. Edwin Paine and Charles Rowland, a dead boy and a dying boy, show us that we don’t have to stay anywhere forever.

Harlan Ellison introduces this volume with a pointed essay on perfection and excellence.

(DC Comics, 1992)