I’ve remarked before on Morton Feldman’s propensity to shape sound with silence, a tendency he shares with Toru Takemitsu. Listening to Feldman’s Piano and String Quartet, a late work, written two years before his death in 1987, I realize that the juxtaposition of sound and silence in Feldman’s work is only the tip of the iceberg, so to speak.

I’ve remarked before on Morton Feldman’s propensity to shape sound with silence, a tendency he shares with Toru Takemitsu. Listening to Feldman’s Piano and String Quartet, a late work, written two years before his death in 1987, I realize that the juxtaposition of sound and silence in Feldman’s work is only the tip of the iceberg, so to speak.

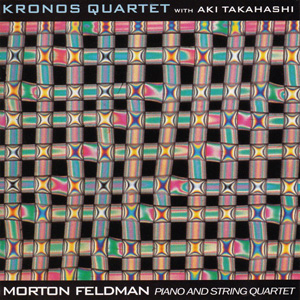

The piece is one extended movement that generally runs between 80 and 90 minutes; this performance, by Aki Takahashi on the piano with Kronos Quartet (David Harrington, violin; John Sherba, violin; Hank Dutt, viola; Joan Jeanrenaud, cello), runs just shy of 80 minutes.

And how to describe it? It’s deceptively simple, an extended series of small progressions and arpeggios on the piano, accompanied and punctuated by brief chords from the quartet. The rhythm doesn’t vary appreciably, the volume is just above sotto voce, and the sonic resources are severely restricted. I’ve seen this piece referred to as “minimalist,” but it’s not the serial minimalism of Riley, Glass, or Reich: that comes from Javanese gamelan and is, comparatively, very rich and complex. In Feldman’s Piano and String Quartet, the complexity is all in your head: it builds and bleeds off tension. depending on how closely you are listening to it. The closest parallels I can think of are the paintings and sculpture of Sol LeWitt or Donald Judd, or the plays of Samuel Beckett.

And there are several ways to approach this music. One can listen closely, marveling at the fragility of the composition, the spareness of the sound, the sheer intellectual discipline of the work itself (and the performance), or one can simply let the music permeate the space, supplying an ambience. I actually find it relaxing enough that I play it while dozing – it seems particularly suited to that place halfway between sleep and waking.

Unlike some of Feldman’s other works, this is not particularly visual. It’s much more a thing of time and space, of intervals, even context: this is one of those instances in which what you are going to get from it depends greatly on what you bring to it.

Kronos Quartet has a solid reputation as one of the pre-eminent contemporary music ensembles, and Takahashi was one of Feldman’s favored pianists during his life. It shows, I think: the piece is handled delicately but confidently, and comes through with its fragility not only intact, but transmuted into strength.

I don’t know if I’d recommend this as an introduction to Feldman. Something like Rothko Chapel or The Viola in My Life is going to give a newcomer rather more to hold on to, but once you’ve cut your teeth, so to speak, it’s a work that certainly rewards the time you spend on it.

(Nonesuch, 1993)