It’s tempting to say that comics underwent a radical transformation in the 1960s and ’70s. They didn’t. What did happen was that comics as a medium, with the rise of underground comics through the agency of R. Crumb and his peers, underwent a radical expansion of style, genre, and subject matter as an addition to the “mainstream.” Part of that was the advent of what Justin Hall, in No Straight Lines, has termed “queer” comics.

It’s tempting to say that comics underwent a radical transformation in the 1960s and ’70s. They didn’t. What did happen was that comics as a medium, with the rise of underground comics through the agency of R. Crumb and his peers, underwent a radical expansion of style, genre, and subject matter as an addition to the “mainstream.” Part of that was the advent of what Justin Hall, in No Straight Lines, has termed “queer” comics.

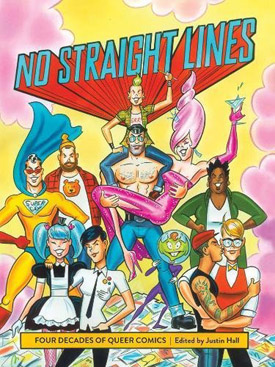

The term “queer” in this context, as opposed to “gay, “lesbian,” “LGBT” or any other term that might denote the gay and trans communities in the wider sense, is meant to incorporate a particular viewpoint. As Hall defines it, queer comics are “comic books, strips, graphic novels and web comics that deal with LGBTQ themes from an insider’s perspective.” In other words, while mainstream comics may assimilate LGBTQ characters (which has been happening more and more in recent years), queer comics look at the community, the identities and the experience from the inside. Hall has quite wisely set a limit on the scope of this inquiry, including literary (as opposed to pornographic) Western comics with stories and examples that could be presented full-length within the limits of a single volume. If you’re looking for the origin of Northstar, Batwoman, and their peers, this is not the place.

Hall has sketched a succinct history of queer comics, beginning with the early harbingers in “Comics Come Out.” He counts as first among them Touko Laaksonen, the Finnish artist who went by the name of Tom of Finland, and whose cartoons of hypermasculine, phenomenally well-endowed men left nothing to the imagination. The key element in this stage of the history of queer comics is best summarized in a comment by Alison Bechdel, one of the best-known creators: “I had set out . . . to make lesbians visible.” That holds true, I think, for the movement as a whole.

The key date here is 1969, the Stonewall Riots, which marked not only a shift in the posture of the LGBT community, but the rise of an open gay subculture. As a natural consequence, more and more gay newspapers sprang up, and they ran comics, providing a wealth of outlets for the emerging artists in the genre while also linking artists and community more closely, as Hall points out in “File Under Queer,” subtitled “Comix to Comics, Punk Zines and Art During the Plague.” The decade of the 1980s witnessed the AIDs epidemic and the linking of the more radical elements of queer culture to punk culture, culminating in “homocore,” later “queer core” — basically, a movement designed to annoy everyone. An explanation, of sorts, is provided by comics historian Sina Shamsavari:

These cartoonists were of course critical of homophobia, but far less concerned with affirming a sense of shared gay identity and community, and much more concerned . . . with critiquing mainstream gay culture as conformist and commercialized, and with creating an alternative version of queer life and culture.

“A New Millenium” notes the increasing presence of transgender artists and themes, and the explosion of new media: blogs and web comics (as well as video web series) increased the possibilities of reaching an audience — and that means almost any specific audience — exponentially. And ironically enough, this rebellious alternative movement seems to have come full circle with the creation in 2010 of Bent Con, which is just what you might imagine: a queer comics convention.

The remainder of the book is composed of examples of queer comics, organized to follow the chapters in Hall’s essay. There are two obvious elements that these comics have in common: these are “no holds barred” stories, and there’s a strong element of satire, which is only to be expected when reality butts up against stereotype. There’s also a fair amount of anger, especially in those focusing on the AIDS crisis.

No Straight Lines is, I think, more valuable for the comics than for the essay. That part of the book represents a broad selection of themes, approaches, and attitudes, although the sheer numbers are overwhelming. I would have appreciated a longer essay with more analysis and firmer linkages to the queer comics movement and the wider culture, both gay and straight. These are, after all, political acts, part of the give and take of American culture during the latter portion of the twentieth century. After all, context is a defining feature in the history of any cultural phenomenon.

But in spite of my reservations, I’m willing to give No Straight Lines high marks just for existing.

(Fantagraphics Books, 2013)