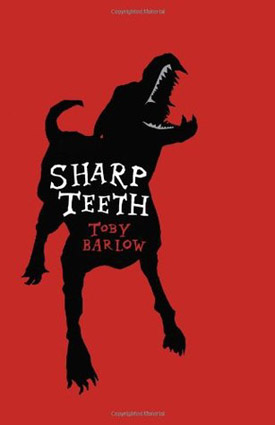

I’ve had one previous experience with fantasy in verse (well, unless one counts the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the like), and it wasn’t a happy one. Nevertheless, when Toby Barlow’s Sharp Teeth crossed my desk, I screwed my courage to the sticking point, as they say, and I’m happy to report that my valor was justly rewarded.

I’ve had one previous experience with fantasy in verse (well, unless one counts the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the like), and it wasn’t a happy one. Nevertheless, when Toby Barlow’s Sharp Teeth crossed my desk, I screwed my courage to the sticking point, as they say, and I’m happy to report that my valor was justly rewarded.

This is a story about werewolves that pretty much sets our expectations of that genre aside. First, the wolves don’t necessarily turn into wolves — they turn into dogs, which Barlow makes believable, and which also saves some head scratching on the part of the supporting cast: a dog running loose on the street is a lot less noteworthy than a wolf.

There are four packs involved here, and it’s basic to the story that the social construction mirrors that of dogs: the packs have their territories, and, inevitably, boundaries get transgressed. It also follows that form within the packs, since there is one leader, who can be challenged, but you do so at your own risk — losing is pretty final.

Did I mention that these creatures tend to eat people who get in their way?

The center is Lark Tenant and his pack. Lark is a lawyer, and a successful one. He’s also a long-range planner, with goals in sight that only he knows. His pack keeps a low profile and stays out of the really dirty stuff, the stuff that can get you noticed. Just an occasional hit, very low-key. Lark also sends agents to infiltrate other packs, and that’s when trouble starts: Baron, his lieutenant, turns, and the pack is attacked one night while Lark is away. Some dead, some fled, and some — including Baron, who set it up — co-opted into the new pack. But Lark is still at liberty, and “She” (she has no other name), the pack’s alpha female, is also free and able to work out her own agenda. Lark starts assembling a new pack.

First things first, because I know you’re sitting there saying “Verse? A werewolf story in verse?” Yes, and very accomplished free verse at that. Stop thinking about Shakespeare and Marlowe — this is totally contemporary diction, smooth and seamless, and easier than reading prose. Barlow’s made use of the verse to enable a kind of delivery that simply wouldn’t work in prose, one that leaves room for digressions and ruminations that would interrupt the flow in any other kind of writing. And yet the diction is, in a very real sense, “poetic” — the spaces between the words work as much as the words do, the juxtapositions, the elisions, all come together in a picture that’s much richer than you expected it to be. It’s better than good.

And when the pack is dissolved, the story sort of explodes. Lark finds refuge, rescued from the pound by a woman who needs rescue herself, but it gives him scope to work. “She” has her own agenda, part of it involving a dogcatcher with whom she falls in love. (The dogcatcher, Anthony Salvo, is the intersection of several plot lines.) The new pack has its own problems, with Baron, who sold out Lark’s pack, taking over, not by open challenge but by subterfuge and ambush. It’s a cinematic structure, cutting from scene to scene, and builds up a lot of momentum. And there’s a police detective, Peabody, conducting an investigation that includes illegal dog fighting, missing persons, and the dog pound at which Anthony works. And the writing is strong enough that, if you’re at all prone to picture what you’re reading in your imagination, it’s like watching a movie.

Barlow has done some masterful character building here. “She” is a stunning case in point: we’re never given her name, but we know her history, we start to understand her motives, and whenever the story shifts to her, there’s no doubt as to who it’s about. When it comes right down to it, she doesn’t need a name because she’s become such a potent presence. This holds true across the board, with Lark, with Baron, with Mr. Venable, who has influence in places you don’t necessarily want to know about, with everyone we meet: they are vividly drawn.

I should point out that it’s not an easy book to read, not because of the verse or the formal aspects or anything along those lines. It’s pretty dark, the people are not particularly nice, there’s enough grit to satisfy the most jaded appetite, and unpleasant things happen to people, often in messy ways.

It’s a strong book, absorbing, exciting, and more than good. And there’s a plus, if you need one: it’s part of Harper’s “P.S.” line, with an author interview, a cast list (I told you it was like a movie), a quiz (“Is Your Dog A Werewolf?”), a playlist (seriously), and something called “The Book Brahmin Questionnaire,” whatever that is.

(Harper, 2007)