I’ve sort of lost track of Star Trek, after being glued to the TV every week in my younger days, as Gene Rodenberry’s original series was airing. Strangely enough, the last Star Trek movie I saw was The Wrath of Khan. (If that’s a spoiler, well, life is like that.) Let me say right off the bat that Star Trek: Into Darkness is not that.

I’ve sort of lost track of Star Trek, after being glued to the TV every week in my younger days, as Gene Rodenberry’s original series was airing. Strangely enough, the last Star Trek movie I saw was The Wrath of Khan. (If that’s a spoiler, well, life is like that.) Let me say right off the bat that Star Trek: Into Darkness is not that.

It seems that one John Harrison has declared war on Star Fleet. It doesn’t take long to figure out that “John Harrison” is not his real name, and it seems that he has what to him are good reasons for his vendetta. His real identity and those reasons provide the basis of the story, as Capt. James T. Kirk (Chris Pine) and the crew of the starship Enterprise start off in pursuit, armed with 72 specially modified torpedoes. Their orders are simple: find him (he happens to be on the Klingon homeworld) and eliminate him. It’s not going to be easy to pull this off: the likelihood of open war between the Klingon Empire and the Federation is all too high if they’re discovered. And they’re not the only ones aware of this.

Let’s start with the basics: the script is admirable, tight and focused, and the subplots are kept firmly under control. And we have preparation for the revelations (and oh, yes, there are revelations) and the reversals (plenty of those, too), not blatant, but they’re there. One never gets the feeling that the writers (Roberto Orci, Alex Kurtzman, and Damon Lindelof) reached into their stash of plot twists to keep the story going.

There’s a good balance to the mood and tone, enough so that the funny parts are funny, the poignant parts grab at you, and the edge-of-the-seat parts keep you right where they want you.

Which brings us to the cast. Stellar. This is a younger Enterprise crew, and there’s less of that “professional cool” I remember from the early TV series and films. Chris Pine’s Kirk is not William Shatner’s Kirk — more openly headstrong, more openly rebellious, and equally stubborn, with a heavy dose of idealism. The same goes for Zachary Quinto’s Spock — yes, it’s Spock, but not the Spock I remember. Anton Yelchin as Chekhov made quite an impression: he’s young, he finds himself thrown into a situation in which he’s barely treading water, and it’s all there, the insecurity, the determination, the panic, the overriding need to handle it. And I have to mention Benedict Cumberbatch, who is a major reason I wanted to see this one after seeing him in the TV series Sherlock and couple of other roles. Cumberbatch’s Khan is not Ricardo Montalban’s Khan. (Yes, “John Harrison” is Khan.) Cumberbatch doesn’t bother with bluster, and he’s really, really scary, a study in cold purpose fueled by deep anger, driven past the point where questions of honor and fair play might matter. (I find myself wondering whether the casting director took physical appearance into account: Pine starts to look more and more like Wiliam Shatner, Quinto bears an even stronger resemblance to Leonard Nimoy, and Karl Urban could conceivably be a younger DeForest Kelley.)

Director J. J. Abrams has kept this one on course. There are a couple of scenes that could have been tighter, where the momentum falters, but only by a little: the film grabs you and holds you from the earliest scenes, clues are apparent without being blatant, the emotional continuity is coherent and believable. It’s a beautifully constructed film, and it’s to Abrams’ credit that no single element ran away with it.

Those who love science-fiction (including Yours Truly, from an early age) have been, at the very best, ambivalent about Star Trek‘s various incarnations in film and television. Those adaptations often wound up being formulaic, trite, and not very imaginative, and all too often missed the most important thing: science fiction has always been a literature of ideas, of explorations starting with the question “What if. . . ?” Gene Roddenberry managed the substance, posing sometimes difficult questions in the context of space opera, not usually considered the most profound of sub-genres. It worked for him and it’s worked for Abrams.

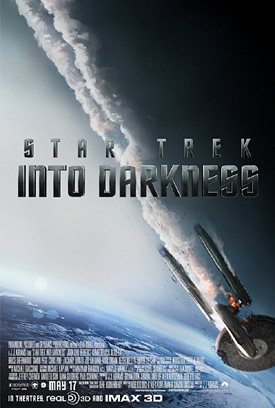

(Paramount Pictures, Skydance Productions, Bad Robot, 2013; for full credits, see IMDb.)