In case anyone doesn’t know, the mysteriously reclusive science-fiction writer James Tiptree, Jr., whose writing was cited by no less than Robert Silverberg as “ineluctably male,” was in fact Alice Sheldon, who, during the course of her somewhat unconventional life, had explored Africa as a child with her parents, been an art critic, was one of the first women to go through the Army Intelligence School, and, when she left the CIA, returned to school for a Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology.

In case anyone doesn’t know, the mysteriously reclusive science-fiction writer James Tiptree, Jr., whose writing was cited by no less than Robert Silverberg as “ineluctably male,” was in fact Alice Sheldon, who, during the course of her somewhat unconventional life, had explored Africa as a child with her parents, been an art critic, was one of the first women to go through the Army Intelligence School, and, when she left the CIA, returned to school for a Ph.D. in Experimental Psychology.

Tiptree’s career, as much as her writing, led to the creation in 1991 of the James Tiptree, Jr. Award by Pat Murphy and Karen Fowler. As Murphy says in her introduction to the first anthology, “We did it to make trouble. To shake things up. . . . And to honor the woman who startled the science fiction world by making people suddenly rethink their assumptions about what women and men could do.” (The introductions to both volumes, by Murphy, Fowler, and Debbie Notkin, by the way, are wonderful — deft, funny, tough and unregenerately subversive, they give a history of the Award and of the way it is decided every year. Apparently, each panel of judges is making it up as they go along, at least as far as the criteria for selection are concerned.)

The Award is “presented every year to a short story or novel which explores and expands gender roles in speculative fiction.” And the stories come at gender from every direction. Geoff Ryman’s “Birth Days,” which opens the first collection, is a series of snapshots at ten-year intervals that begin with the development of techniques of gene surgery that can “cure” homosexuality in adults to the discovery that homosexuality is a back-up reproductive strategy that suddenly has value as gay men become an endangered species. The conclusion of Anthology 1 is a mini-trilogy composed of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Snow Queen,” with its reiteration of “acceptable” roles for girls and boys, and two brilliant variations, Kara Dalkey’s evocative “The Lady of the Ice Garden,” and Kelly Link’s brash and edgy “Travels with the Snow Queen.”

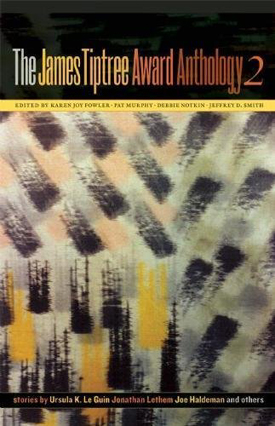

The second anthology is equally rewarding, including one of Ursula K. LeGuin’s subliminally poetic tales, “Another Story, or A Fisherman of the Inland Sea,” a wonderful speech by Nalo Hopkinson, “Looking for Clues,” all about looking for ourselves in the images of popular culture (and that one speaks to a much broader audience than Black girls growing up in the Caribbean), an amazing letter, almost as breathless in places as Gertrude Stein, from Tiptree to Rudolf Arnheim, and another reminder of why I like Jonathan Lethem so much.

The second anthology is equally rewarding, including one of Ursula K. LeGuin’s subliminally poetic tales, “Another Story, or A Fisherman of the Inland Sea,” a wonderful speech by Nalo Hopkinson, “Looking for Clues,” all about looking for ourselves in the images of popular culture (and that one speaks to a much broader audience than Black girls growing up in the Caribbean), an amazing letter, almost as breathless in places as Gertrude Stein, from Tiptree to Rudolf Arnheim, and another reminder of why I like Jonathan Lethem so much.

There is not one story, excerpt, letter, essay, what-have-you, in either volume that I disliked. True, there were some that I liked more than others (and cheers to LeGuin for her in-your-face speech about genre fiction and the increasingly tenuous boundaries that hold the genres separate [“Genre: A Word Only the French Could Love”]), but there is not one bad offering in the lot.

There are also, for the historically inclined, lists of the winners, the short-listed works, the long-listed works (no “nominees,” which the Motherboard feels automatically creates a group of “losers”), all destined for my lengthy and growing “to read” list.

Mind you, I am not partial to theme anthologies (“100 Poems So Sweet They Make Your Bridgework Hurt”), but I am very happy these two books landed on my desk.

(Tachyon Publications, 2005)

(Tachyon Publicvations, 2006)