It’s something of a paradox: As a collection I found this volume kind of weak, but there are a lot of very fine stories in it. So many, in fact, that on going back over the anthology a second time, I wondered why I’d thought it was weak in the first place. As a reader, I’d probably just leave it at that; but as reviewer, I feel I owe it to my adoring public to tell you precisely why I feel the overall effect is weak. So I dove back into the book for a third time. Such travails are how I earn my fabulously high salary here.

It’s something of a paradox: As a collection I found this volume kind of weak, but there are a lot of very fine stories in it. So many, in fact, that on going back over the anthology a second time, I wondered why I’d thought it was weak in the first place. As a reader, I’d probably just leave it at that; but as reviewer, I feel I owe it to my adoring public to tell you precisely why I feel the overall effect is weak. So I dove back into the book for a third time. Such travails are how I earn my fabulously high salary here.

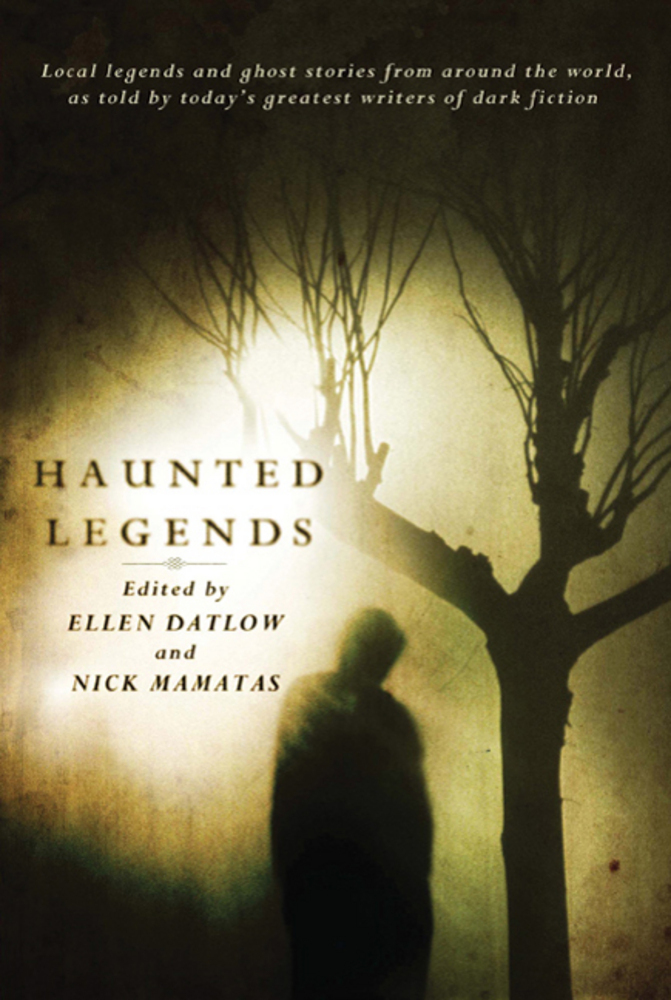

The theme of the collection is straightforward enough: Datlow and Mamatas asked for local spooky legends and ghost stories, written not by the usual campfire storytellers, but by serious writers. You know the drill. They got some big names and some not-so-big names, and a considerable range of tales. It’s guaranteed to be a mixed bag of goodies, of course. And yet . . .

Dep’t. of Personal Taste: it may help if you like horror fiction, really, and for the most part I don’t. (More on that later.) I just like anthologies with Ellen Datlow’s name on them, whoever she’s teamed up with this time around: whatever else, I’m going to be introduced to the work of at least one hitherto unfamiliar writer whose art and craft will impress the hell out of me. Guaranteed. On top of that, as far as this book goes, I am endlessly fascinated with local traditions and legends. And I’m always interested to see what an author can do with a piece of genuine folklore. So, with all of the above in mind, let’s take my nickel tour of (mostly) the high points of Haunted Legends.

My issues with the collection start with the fact that I was five stories in before I got to anything that grabbed me. By the time I reached Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “Red As Red,” I was feeling moderately grey. And hers is a grey little New England tale, too — but it lives up to its title all the same. It’s tidily crafted and strikes a lovely balance between revelation and mystery. It is also told in the present tense, which tends to annoy the hell out of me, but didn’t here. Kiernan’s art is well enough developed that apparently she can pull off some don’t-try-this-at-home effects. A tip o’ the hat, ma’am.

Hard on the heels of this gem is Ekaterinia Sadia’s “Tin Cans” — a painful exhumation of guilt and personal helplessness amidst the bones — both figurative and literal — of the U.S.S.R. How many young women really did disappear into Beria’s mansion? The twists in the tale are hardly surprises, and Sadia doesn’t play them for shock value. They come out like secrets you didn’t want to remember, not dazzling revelations. It’s not a young person’s story; old age and old guilt seep from this piece and settle damply, numbly into your bones. To Ekaterina I would bow; but she leaves me feeling as though my knees are too stiff with years to rise to the occasion without my cane.

I observed that I don’t generally care for horror. One reason for it is simply that fiction listed in that category rarely succeeds in evoking the true emotion in me. John Mantooth’s “Shoebox Train Wreck” is a signal exception, and not the only one in the book. This low-key first-person exploration of a life lived in guilt over a fatal collision isn’t bloody; it’s not dangerous; it won’t leave you worried about noises in the night … but a slow, sad horror crept into my heart while I read this one, and there it lingered. “The dead do not haunt the living.” This faint whisper is introduced on the second page, so it’s hardly a spoiler; and the premise is not precisely original, but Mantooth’s dispassionate, careful eloquence brings the man’s obsessive guilt to life from the gut.

The worst problem with the book as a whole is that for me, at least, in most cases it took reading the authors’ afterwords for me to become interested in the legends on which they were based. And at that point, as often as not I found the footnotes more interesting than the tale. However, “Fifteen Panels Depicting the Sadness of the Baku and the Jotai” (with which Catherynne M. Valente earns incidental honours for the longest title in the anthology), is an artistic exception to this pattern. Her footnotes just made me want to go back and reread this uncommon little gem of cross-cultural mythcraft.

Those four tales in sequence set the pace and the level of quality I like to see in an anthology. But after that come another couple I found … not bad, just not all that interesting. I won’t dwell on ’em, you might like them better than I. Still and all, from there on out the book becomes a little hit-and-miss.

Several of the efforts in this collection feel forced, as though some author had a situation or character in mind already and figured out a way to shoehorn in a local tradition from someplace or other. Some of the authors I was most looking forward to let me down. Joe R. Lansdale has never failed to please me in his comics scripts, but “The Folding Man” just felt kind of flat. As though it needed to be, well, unfolded some more in order to really be a story. Sorry for the cheap shot; Lansdale’s wasn’t the only story that left me with more or less that feeling, but his title brings the issue into the best focus. Ramsey Campbell left me even flatter with “Chucky Comes To Liverpool.” When you consider that Lansdale and Campbell give us the last two stories in the book, this is a tad unfortunate. What I found was a book where the strongest part was the second quarter, a matter of editorial pacing which left me with a worse overall impression than the book may really deserve.

Because there are some definite high points. “The Redfield Girls,” for example. The worst thing I can say about this piece by Laird Barron is that I’m not sure what kind of story it is. I do know that whatever it is, it’s a very good one. The characters have life and depth. And death. And it came closer to giving me nightmares than any other tale in the book. Deep water and cell phones. Generations of women and old friendships. Winding mountain roads. Brrr. I actually don’t recommend reading this one late at night by yourself.

So it’s between Barron and Jeffrey Ford for the prize in this lot for carrying the cleanest flavour of local spookiness. Ford’s “Down Atsion Road” has all the rambling development of true local ghost stories, as our first-person narrator — ostensibly Ford himself — explores New Jersey’s Pine Barrens and the people living … or once living … in the region. (He also takes major bonus points for not going for the obvious and spinning us some yarn about the Jersey Devil). In fact, Ford avoids the obvious throughout the piece. It takes its time, it meanders, and yet there really isn’t a spare word in it. It all builds to his quiet punch line — and it’s a terrific one. Here’s another story where the author’s afterword was not only fascinating in its own right, but actually heightened my enjoyment of the story — another bonus point.

Erzabet Yellowboy’s admirable contribution, “Following Double-Face Woman,” strikes me as kind of a cheat in this collection. Drug parable in the guise of an extended lyrical metaphor, Yellowboy takes the mythic Amerindian figure of a half-lovely seducer who only shows her ugly face after the clinch and draws for us a clean, spare portrait of methamphetamine abuse among modern Indian youth. Did it belong in a book of local spooky myths and ghost stories? I dunno. It struck me as out of key with the nominal chord. But that quibble aside . . . The story’s got real punch, and Yellowboy pulls none of it. The story preaches, but Yellowboy preaches so artistically that she makes her point in spite of that. As far as the footnotes — excuse me, afterword notes — go, my worst quibble is that Yellowboy doesn’t specify which tribe, people, nation or whatnot gives us the legend of Double-Face Woman. Beyond that is the question of Mythical Correctness. Are Indian myths really to be taken on the same scale as local legends or ghosts? Not in my cosmology, I have to say. And yet “Following Double-Face Woman” is a good tale, well constructed both as craft and as art, and it certainly belongs someplace. Like another one or two pieces in this collection, however, I’m not sure it was here.

So, you get the idea. Twenty stories. Six I thought were terrific: pieces that will stick in my head and be welcome there. Two or three struck me as decent, but misplaced for the theme one way or another. (There’s some overlap between those categories, in fact.) I think a few more selections are simply not to my taste, and I hope you like them better than I did. But there are too many pieces in this collection where some good writing and characterisation (in some cases very good indeed) never coalesces into that elusive thing that our hearts recognise as a Tale. In too many others, I don’t think the theme really lit the fire for these writers: they gave it a professional try, but what we get as readers is some local tradition trotted out in narrative form, with no real life to it. So to speak.

My advice? Read it. The high points are well worth the price of admission. But take it as what it is: an uneven collection that lacks overall unity, but has some instances of real artistic merit. Go in with your expectations dialed a little low and it’ll knock your socks off. Because some of those high points are very high indeed.

(Tor Books, 2010)