Handel’s Messiah is without doubt the most often-performed work from the baroque canon, to the extent that every December sees concerts organized by symphonies, choruses, churches, and even sing-alongs staged by volunteers. Think about it: it’s almost one word: Handelsmessiah.

Handel’s Messiah is without doubt the most often-performed work from the baroque canon, to the extent that every December sees concerts organized by symphonies, choruses, churches, and even sing-alongs staged by volunteers. Think about it: it’s almost one word: Handelsmessiah.

Handel himself is on the one hand very well-known, and on the other somewhat of a cipher: very little has survived that gives us any real insight into the workings of his mind, and his personal life is shrouded in mystery, unlike that of his exact contemporary Johan Sebastian Bach. Born in Germany, Handel displayed his talents as a musician at an early age, although is father insisted that he study law, for some reason not trusting the stability of the musical life. On his father’s death, however, Handel left his law studies, spent some time in Italy, and wound up in the Hanoverian court of England, where he enjoyed success as a composer with royal and aristocratic patronage. Strangely enough, although known for his great oratorio and several works of festival music, he was mainly a composer of operas, many of which have been revived and recorded. (John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, in fact, was created in part as a satire on Handel’s opera seria.)

That Handel was a master of his craft is without doubt. Brace yourself: Messiah, one of the greatest works of Western music, was composed in about three weeks, from August 22 to September 14, 1741, a rather staggering accomplishment. It is also an ambitious work: although best known for those parts that deal with the birth of Christ, the “Hallelujah” Chorus and the anthem “Joy to the World,” which was adapted from the oratorio, it is nothing less than an explication of the meaning of Jesus, from the anticipation of the Nativity to the victory of the Resurrection.

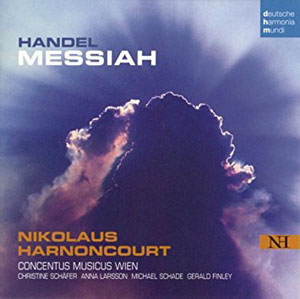

And now we are faced with yet another recording of Handel’s great oratorio. I was gratified on receiving this one in the mail to discover that the conductor is no less than Nikolaus Harnoncourt, who has been a leader for decades in performing music on period instruments and in the context of its time (as much as possible, at least). I would be hard put to think of anyone who has surpassed Harnoncourt as an interpreter of baroque music. In this instance, he has gone back to Handel’s autograph scores, so that this performance is, in all important respects, done the way Handel did it.

Handel said, about Messiah, “Whether I was in my body or out of my body as I wrote it, I know not. God knows.” I don’t know if we can take that as an expression of any particularly deep piety: it was, after all, an age in which God was an integral part of conversation, regardless of depth of belief. Take it, rather, as an expression of the context of composition, a description of what goes on in the artist’s mind in the throes of creation. (I’ve been there: I once tried to explain that, whether I am in the darkroom or the kitchen, my internal dialogue — and it is a dialogue — is likely to be on the order of “this goes there, adjust that, no, this needs to happen. . . .” I think the creative act happens in a place where words just don’t work very well. Handel was actually very cogent about it.)

At any rate, Harnoncourt and the forces he has assembled manage to touch that place. I really was beginning to think I was over baroque music. Perhaps I was just listening to things that weren’t really all that good. This one catches all the magnificence of which the baroque is capable, and also brings in a sense of intimacy that is all too rare. (And that itself is rather anomalous: baroque music was meant for intimate spaces and intimate performances; perhaps we are much too acclimated to large concert halls and casts of thousands.) Clarity is something that is overwhelmingly important in music, and is especially difficult in the baroque, with its elaborate ornamentation. Both the chorus and the soloists pull it off beautifully.

Some spot observations, of necessity somewhat subjective: the duet “He shall feed His flock” for alto and soprano is a beautifully limpid piece, sung with great sensitivity by Anna Larsson, alto, and Christine Schäfer; the following chorale, “His yoke is easy,” is a fluent and seamless section, and “Behold the Lamb of God,” while understated, still projects dramatic tension and manages to soar in the way that only baroque music can. Bass Gerald Finley brings a great deal of power to “Thus saith the Lord,” and tenor Michael Schade, in “But Thou didst not leave,” manages a kind of melting sweetness over the tensile strength of the vocal line.

And the “Hallelujah” Chorus? This is not the overwhelming power of massed voices backed by a full symphony orchestra. This is the famous chorus as Handel’s audience might have heard it, and there are things here that I think we miss in the contemporary concert hall: the power is more subtle, the complexity becomes clearer, and the chorus builds amazing depth as it progresses. It’s just simply beautiful, and all too brief.

There are any number of recordings of Messiah, but this is a very strong entry into a crowded field. It is very revealing of the complexity and depth of Handel’s masterpiece, performed with intelligence, sensitivity and authority.

(Sony BMG/Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, 2005)