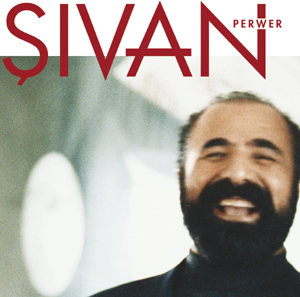

Like so many politically active Third World musicians, Sivan Perwer is an exile from his native Kurdistan, at last report residing in Sweden. He has the distinction of having had his music banned by not one, but three governments. And, like so many musicians in general, he comes from a family tradition of performance, and yet while in school, his studies were strongly oriented toward mathematics.

Like so many politically active Third World musicians, Sivan Perwer is an exile from his native Kurdistan, at last report residing in Sweden. He has the distinction of having had his music banned by not one, but three governments. And, like so many musicians in general, he comes from a family tradition of performance, and yet while in school, his studies were strongly oriented toward mathematics.

It may seem odd to make this statement about a recording by a Kurdish popular singer, but this album rocks. The opening track, “Sebra Mala,” ostensibly about the plight of Kurdish women through the eyes of an exile, moves along with a richly complex, counterpointed rhythm that is irresistible. It is followed by “Nazdar,” the lament of a poet for the woman who refuses to love him. While lively, there is a seductively melancholy element to the music, underscored by Perwer’s throbbing vocals. These two are typical of the offerings on this album, with a respite, and a distinct change in mood, offered in “Çay Berbena,” a softly lilting ballad about a poet who must leave his home and his love. This is followed by “Yek Mûmik,” a traditional wedding dance, another vividly lively tune with an absolutely amazing, intricate rhythm that demands attention. (There are certain songs, I noticed in the days when I was a party animal, that are so compelling that you find yourself walking in time to them. I used to call them “heartbeat songs.” This is one of them. The urge to dance is almost irresistible.) The one overtly political song on this disc is “Tembûra Min,” written by Perwer; it is a low-key, powerful ballad, beautifully performed.

The entire album reeks of exoticism. As much as the Kurds have been the subject of American news coverage in recent years, I find that I, like most of my countrymen, really have no sense of who they are or what they are about. Perwer’s music brings it to vivid life, not only through the range of songs he performs – not overtly political, but concerned with the things that all popular songs are concerned with, love, loneliness, missing home, problems with parents – but in the very sounds and rhythms. Perwer’s voice, with its strong tremolo and amazing flexibility, manages the wavers and trills that are an intrinsic part of the music of the Middle East and so much of Central and Western Asia flawlessly, with an occasional catch that, I think, owes more to passion than to the difficulty of the music. The musicians (Ismet Alaattin Demirhan, Hassan Kanjo, Najmaldin Nam, and Dealer Saaty) not only support Perwer’s vocals beautifully, but carry the instrumental interludes along with a lilting momentum that is engaging in its own right.

The songs are, to an American audience, rather longer than we are used to: the shortest clocks in at just over five minutes, but ultimately, one doesn’t really notice that, even though the music is strongly repetitive. (Much is made, in some quarters, of the fact that Western popular music relies so much on repetition, cited by some as a poverty of invention. It may have something to do with coming of age in the 1960s, but to be honest, I have never supported this idea, nor seen the sense in it: repetition is a formal element in the structure of a popular song, as it is in any medium that partakes of poetry.) In Perwer’s hands, this repetition of phrasing and melodic fragments builds a hypnotic intensity that gets your heart beating while keeping you engaged enough that you really don’t want to leave the music.

Confession: this CD one of those things that I have been avoiding. On first listening, not only was I not impressed, I was somewhat put off. (Chalk it up to a steady diet of music from everywhere except the West for perhaps too long: I wound up listening to Mahler and Depeche Mode as a form of rebellion.) However, duty dragged my nose to the grindstone, and I’m glad it did: Sivan Perwer is an exceptional experience.

(Caprice Records, 2003)