Me and my gal we sat on the stoop Sat on the stoop, sat on the stoop. Her paw came out and turned me loopty-loop. Sal, won’t you come out tonight? Buffalo gals, won’t you come out tonight? Come out tonight, come out tonight? Buffalo gals, won’t you come out tonight, And dance by the light of the Moon? — Ursula K. Le Guin

Me and my gal we sat on the stoop Sat on the stoop, sat on the stoop. Her paw came out and turned me loopty-loop. Sal, won’t you come out tonight? Buffalo gals, won’t you come out tonight? Come out tonight, come out tonight? Buffalo gals, won’t you come out tonight, And dance by the light of the Moon? — Ursula K. Le Guin

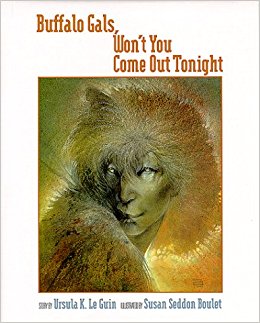

I first read this story as part of an anthology, so I was unprepared for the beautifully illustrated book that arrived in the mail. Susan Seddon Boulet’s illustrations take us into the magical world Gal, or Myra as she is known in some circles, experiences after being injured in a plane crash and then rescued by Coyote. Boulet’s work draws us into the world Gal sees with her new eye, a multilayered field of vision that bridges the nature and the appearance of things so beautifully communicated in Le Guin’s story. It has earned a place next to my treasured “children’s” books — the selfishness of an adult who finds some things to beautiful to actually let the wee wilds grub them up. (Mine! Ahem — They get their own copies whenever possible.)

Le Guin draws her characters from the North American First Nations archetypes centered in the plains and desert regions. With a directness that is both charming and crude, mystical and frank, we enter the world of the People, animals that used to share the world with humans before the New People showed up and started paving over everything. Each of the animals that helps Gal along her path shares its way of life with her according to its nature, yet she develops a child’s love for her new mother, Coyote.

Coyote is a glorious character, one of those rare treats that requires an artist of Le Guin’s mastery to bring over from the formative world. With her, Gal learns to cook with hot rocks and meets a host of characters, such as Blue Jay, a shaman doctor who organizes a healing ceremoney for Gal’s eye, giving her one of pine pitch.

Of course, “A lot of things were hard to take about Coyote as a mother — Coyote and her friend wouldn’t even wait to get on the bed but would start doing that right on the floor or even out in the yard.” Some parents may find that and a few other aspects of Coyote’s lifestyle hard to take, as well. However, in today’s world of too much information about the perils of strangers, most children third grade and above will be familiar with sex, even if they don’t know exactly what it is. Buffalo Gals is written in the tradition of matter-of-fact children’s folk stories of yore, the simple, direct language of books that get carried home in knapsacks to be read by children with help from Mom or Dad.

Like some parents reading this book, Gal finds herself embarrassed by some of Coyote’s antics, like talking to her turds and keeping them all over the yard. She wonders that she is the only one with two names, and since she can see all the people, like Deer and Rattler and Chickadee as people, what do they see her as? In the end, Myra goes home, regretfully and somewhat resentfully, with her new eye and her new vision, to live in the world of humans, as we all must, in the end.

I truly believe that this magical story belongs to children; children who are at the age where they are at risk of developing eyes that only see animals, not People, and who may regret the loss of their first magical vision of the world, while eagerly accepting their new, independent, maturing selves.

I got a gal with a wart on her chin

And her eyes turn out and her toes turn in.

She’s a durn good gal for the shape she’s in.

Sal, won’t you come out tonight? — Trad

(Pomegranate Artbooks, 1994)