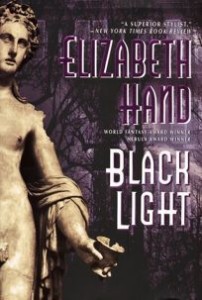

Elizabeth Hand’s Black Light is a foray into the world of dark gods, misty legends, and deep secrets.

Elizabeth Hand’s Black Light is a foray into the world of dark gods, misty legends, and deep secrets.

Lit Moylan (her real name is Charlotte) is about to finish high school. She lives with her parents in Kamensic, New York, a village with a long history and a range of eccentric inhabitants. For the most part, like Lit’s parents, they are theater people, actors, agents, designers, with a leavening of small-town staples, such as the octogenarian Mrs. Langford, who runs the local history museum. There are some odd features of the town, like it doesn’t show up on train schedules or maps, and some parts of the landscape seem to change, just because. Lit and her friends Ali and Hillary take the eccentricities and the general oddness pretty much in stride — this is, after all, home — until the advent of avant-garde film director Axel Kern, owner of the Bolerium, the looming mansion on the mountain, and Lit’s godfather. Axel is accompanied, more or less, by Ralph Casson, who is building the sets for Kern’s latest project, and his son Jamie, who wants nothing more than to get away from it all — the town, his father, everything. And out of nowhere appears Balthazar Warnick, one of the Benandante, the “Good Walkers,” who sees in Lit his lost love from four hundred years before. Lit is much more than that, of course, and not only Balthazar knows it — Ralph is in the know, as is Axel Kern. But then, both of them are much more than they seem.

The story starts off nice and tight and clear — Lit remembers her first meeting with Kern, at a party in his New York loft when she was twelve. She was there with her parents, and the whole thing got pretty weird. And we’re treated to Lit’s take on the absolute normalcy (as far as she’s concerned) of her life in Kamensic, including her friendships with Ali, her best girfriend, and Hillary — she sometimes has sex with him, but nothing like real involvement beyond friendship. There are a few anomalies — the high incidence of suicide, for example, and the number of deaths of children and teenagers, none of which are dwelt on overmuch by the village’s inhabitants. And then Lit starts having visions.

The idea of a cyclic god, the Sacrificed God who dies and is reborn, is probably as old as religion itself, at least those from agrarian societies. He shows up in every mythology that I’ve ever run across, and his death is always a means of regeneration for the world. In Hand’s treatment, we don’t get the idea of regeneration very well — the cycle as portrayed here is rather empty, just a blind re-enactment of events that have happened over and over again through millennia, to the point where they have lost all meaning, graphically illustrated in one very important vision/dream that Lit has toward the end of the book, when she is beginning to understand her part in the story. I think this is part of a larger problem with the book: it seems to have lost focus about halfway through, and became, to this reader at least, a sort of rote recitation. It draws on other icons as well, but doesn’t really establish its own identity — take life in Warhol’s Factory, mix in a little of The Bacchae and some elements of neo-Paganism, and you’ve pretty much got Black Light. The only question is whether Lit will continue the cycle or break it, and that resolution is one of the saving graces of the book.

The core characters — Lit, Ali, Hillary, Jamie, and to a lesser extent Ralph — do come across pretty much as real people, at least enough to give us some connection in the early stages. For the rest, there are a lot of cardboard cut-outs trotting around this book. Strangely enough, a bit player such as Mrs. Langford is vividly sketched with a few decisive strokes, while Balthazar, who has a much more substantial role, seems reduced to a couple of primary obsessions.

It’s kind of a hard call on this one. I am the last to argue against murky atmospherics and dark mysteries, but they have to be portrayed with absolute clarity, and I think this is where Black Light lost me. Once again, I think it’s a case of too many words — when I find myself skimming on a first reading, and realizing that I haven’t missed anything, I think that’s a clear indicator.

Another one for the “casual reader,” I think.

(HarperPrism, 2000)